Two friends of mine both just pointed me to one of the best articles that I’ve read in a long time. It’s called The Expert Mind by Philip Ross in the Aug 06 issue of Scientific American.

The main points are:

* Expertise is Trainable (in the argument of nature vs. nurture, nurture appears to often win in developing experts)

* Expertise is Developed through Practice

* The Practice That Has the Best Results is Repetition with Increased Difficulty (This article emphasizes Anders Ericsson‘s words of “continually tackling challenges that lie just beyond one’s competence.”)

Expertise is Trainable (Nurture Wins!)

In the argument of nature vs. nurture, it seems that each side is always looking for evidence to support it. In this article, the author Ross several times repeats that nurture wins. He bases most of the article on the work of Herbert Simon and on the work of Anders Ericsson, and uses chess throughout as the study case.

Here are some examples of practice proving to lead to expertise (the first two are from a 2001 Economist article):

1) A 26-year-old man could in a few seconds find the fifth root of a ten-digit numeral or could raise a two-digit number to its ninth power. The most interesting part is that he had taught himself how to do such calculation-intensive math by studying math-specific memorization for four hours a day – but having started this only at age 20!

|

2) Ericsson trained volunteers to increase the size of their memory significantly. Regular people can remember up to about seven digits easily. Ericsson trained volunteers in increasing their memory, and after one year of practice, two of the volunteers could remember up to 80 and 100 digits at a time.

3) A third example in both the Economist and the Scientific American article is of Laszlo Polgar, who trained his three daughters to become one masters and two grandmaster at chess. Interestingly, Polgar wrote a book called “Bring Up Genius!” before he had children. Then he followed his own techniques, including giving his daughters six hours of chess exercises per day. The youngest is now the 14th best chess player in the world. |

Expertise Through Practice. (Not All Practice is the Same.)

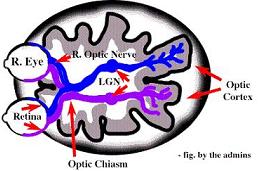

Increasing “Chunking”. Increasing the Quality of Connections.

|

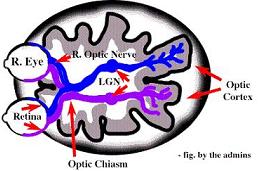

Now the article gets a little more involved, but I’ll give you just the summary here. How are experts able to remember and recall so much more information, and with such detail and complexity? There’s the Herbert Simon concept of chunking: this means, for example, grouping several different chess game openings into one. Or if you’re a chef, grouping several different ways that you might serve tomatoes into a list of the five best ways. |

Using chunking, you are creating a memory “well-organized system of connections,” describes Philip Ross. And the brain remembers best in maps.

Using those well-organized connections, expert chess players are able to look quickly at a chess board that’s had a game in process and even if you were to overturn the pieces, the experts would be able to quickly reconstruct where the pieces had been. But…! (and here’s an example from the article) if you “asked players of various strengths to reconstruct chess positions that had been artificially devised–that is, with the pieces placed randomly on the board–rather than reached as the result of master play,” the opposite would happen! When it came to randomly arranged pieces, the chess experts did not recall the placement of the pieces any better than the amateurs, and in fact, they recalled the placement worse than the amateurs! Because the chess experts were used to recalling piece placements in chunks.

(Here I’m not summarizing, but this is my favorite example from the entire article!)

|

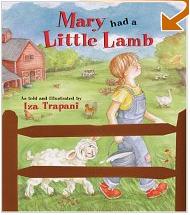

“Take the sentence “Mary had a little lamb.” The number of information chunks in this sentence depends on one’s knowledge of the poem and the English language. For most native speakers of English, the sentence is part of a much larger chunk, the familiar poem. For someone who knows English but not the poem, the sentence is a single, self-contained chunk. For someone who has memorized the words but not their meaning, the sentence is five chunks, and it is 18 chunks for someone who knows the letters but not the words.” |

10,000 Hours and 10 Years

In this 1994 NYTimes article on Peak Performance, author Daniel Goleman describes Herbert Simon’s and Anders Ericsson’s research on expertise. Goleman writes, “The old joke — How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice — is getting a scientific spin.” Ericsson’s research led him to conclude that virtuoso violin performers often have 10,000 hours of practice by the time they are in their early 20’s. Ross in the SA article writes, “Simon coined a psychological law of his own, the 10-year rule, which states that it takes approximately a decade of heavy labor to master any field. ”

10,000 hours or 10 years. This has come to be a calling card for expert knowledge: the 10/10,000 rule.

Dave Seah breaks down the 10,000 hours into more manageable groupings, and he has fun ideas on how to use those hours towards becoming your own “niche” of expert. Alvin describes the trainable structure of expertise and discusses how to increase the impact of your training through – suprisingly and very interestingly to me – your five senses.

Best Practice: Repetition with Increased Difficulty

|

One of my friends who pointed out this article to me said, “it’s not about hitting a golf ball 100 times, it’s about hitting each time at the edge of your abilities.” At that edge, at the brink of challenge, that’s where you can grow. So the best thing you can do to improve within a field is to have an incredible coach, who can lead you along your brink of challenge – or to keep yourself on a very increasingly difficult carefully-paced training system.

Ericsson says that what matters is not experience but “effortful study” and specifically “continually tackling challenges that lie just beyond one’s competence.” |

So, in summary,

expertise is trainable at any age,

practice, practice, practice,

and increase the difficulty continuously!